* * *

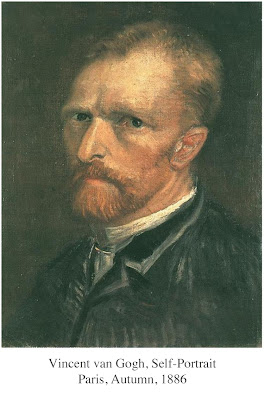

Vincent van Gogh

On 24 June 1907, while working in Paris as secretary to Rodin, Rainer Maria Rilke wrote his wife, Clara: “After all, works of art are always the result of one’s having been in danger, of having gone through an experience all the way to the end, to where no one can go any further. The further one goes, the more private, the more personal, the more singular an experience becomes and the thing one is making is, finally, the necessary, irrepressible, and, as nearly as possible, definitive utterance of this singularity...”

No other artist, perhaps, worked so closely with danger as Vincent van Gogh; no one else experienced the beauty and terror of nature so deeply as the Dutch art dealer-turned-preacher-turned Post-Impressionist painter. That is the quality he shares with the Modernist/Expressionist Prague-born German poet. That is the quality that the young Rilke recognized as being similar to his own creative impulses and longings.

In October 1907, a friend lent Rilke a portfolio of forty reproductions of van Gogh’s work. Rilke studied them thoroughly, and “gained such joy and insight and strength from them” that he felt the intensity of the artist’s presence over his shoulder, “that dear zealot in whom something of the spirit of Saint Francis was coming back to life.” Van Gogh wrote “the best way to know God is to love many things” and “how very fundamentally wrong is the man who does not realize he is but an Atom!” Rilke could have penned either of those statements. Both men had turned their backs to the religion of their forefathers, and both felt an innate sympathy for all that was spiritual in Nature. Van Gogh wished to express poetry in his drawings. Visual art gave Rilke the precise, visceral language he needed to describe the nearly indescribable. What the young poet found in the paintings, drawings, and lithographs he took into himself for several days that fall was less an influence than an affinity: the renunciation of the Self into Art, how van Gogh’s “love for all... things is directed at the nameless,” a “great splendor” that came from “within.” He saw how an old horse could be portrayed in a way that was “not pitiful and not at all reproachful: it simply is everything they have made of it and what it has allowed itself to become” (a feeling Rilke was to convey in “Oh, this is the animal that never was”). He saw how a chair “of the most ordinary kind” could be elevated to the sacred. He saw that he was not the only one who had gazed in awe upon the stars and found them searing.

Many thanks to Ruth and Lorenzo for asking me to contribute these few words to their blog. All errors of fact or supposition are mine alone. ~ ds (of third-storey window)

* * *

Paul Cézanne

For several weeks in the fall of 1907, Rilke returned to a Paris exhibition of works by Post-Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne, Salon d'automne, a memorial to the artist who had died the previous year. During this time of studying the paintings, Rilke wrote his own memorial to Cézanne and his new way of painting (balancing abstraction with realism) in letters to his wife Clara. The letters reveal the influence Cézanne’s work had on his own work: writing poems. Like Rodin, Cézanne was Rilke’s teacher of intense observation. He learned to do with language what Cézanne did with paint, capturing the outer color, light and quality of an object, and drawing the observer into their interior, and maybe more importantly, pulling the outer world into the observer’s own interior. This from the letters:

For several weeks in the fall of 1907, Rilke returned to a Paris exhibition of works by Post-Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne, Salon d'automne, a memorial to the artist who had died the previous year. During this time of studying the paintings, Rilke wrote his own memorial to Cézanne and his new way of painting (balancing abstraction with realism) in letters to his wife Clara. The letters reveal the influence Cézanne’s work had on his own work: writing poems. Like Rodin, Cézanne was Rilke’s teacher of intense observation. He learned to do with language what Cézanne did with paint, capturing the outer color, light and quality of an object, and drawing the observer into their interior, and maybe more importantly, pulling the outer world into the observer’s own interior. This from the letters:“Today I went to see his pictures again . . . one feels their presence drawing together into a colossal reality. As if these colors could heal one of indecision once and for all. The good conscience of these reds, these blues, their simple truthfulness, it educates you . . . “

" . . . scales of an infinitely responsive conscience . . . which so incorruptibly reduced a reality to its color content that that reality resumed a new existence in a beyond of color, without any previous memories.”

The lively and fragrant colors of Cézanne’s paintings that we pair with Rilke passages are another way of illustrating the beyond that Rilke sees. ~ Ruth

* * *

Auguste Rodin

|

| Auguste Rodin, 1911. Photogravure by Edward J. Steichen |

On August 1, 1902, on the eve of meeting the sculptor, Rilke wrote to Rodin:

We will be using the "bread and gold" of Rodin sculptures to illustrate the daily posts intermittently throughout the year. An excellent source for such images can be found here. ~ LorenzoMy Master,... I wrote you from Haseldorf that in September I shall be in Paris to prepare myself for the book consecrated to your work. But what I have not yet told you is that for me, for my work (the work of a writer or rather of a poet), it will be a great event to come near you. Your art is such (I have felt it for a long time) that it knows how to give bread and gold to painters, to poets, to sculptors: to all artists who go their way of suffering, desiring nothing but that ray of eternity which is the supreme goal of the creative life.

* * *

Leonid Pasternak

Russian painter Leonid Pasternak (in the self portrait here, with his wife), the father of novelist Boris Pasternak, met Rilke when he visited Russia with his dear friend Lou Andreas-Salomé. (Leonid Pasternak's son Boris actually translated works of Rilke's into Russian, a language Rilke very much wanted to learn.) It is Pasternak's portrait of Rilke on the cover of the book A Year With Rilke. Pasternak was one of the first Russian painters to consider himself an "Impressionist." He most famously illustrated his friend Leo Tolstoy's novels, for which he received a medal at the 1900 World Fair in Paris. After his visits to Russia with Lou Andreas-Salomé, Rilke embraced Russia as his spiritual heartland and even wanted to take his wife Clara Westhoff to live there. As it turned out, he moved to Paris instead, and became secretary to another artist, who will be featured in future posts here at this blog. ~ Ruth

Russian painter Leonid Pasternak (in the self portrait here, with his wife), the father of novelist Boris Pasternak, met Rilke when he visited Russia with his dear friend Lou Andreas-Salomé. (Leonid Pasternak's son Boris actually translated works of Rilke's into Russian, a language Rilke very much wanted to learn.) It is Pasternak's portrait of Rilke on the cover of the book A Year With Rilke. Pasternak was one of the first Russian painters to consider himself an "Impressionist." He most famously illustrated his friend Leo Tolstoy's novels, for which he received a medal at the 1900 World Fair in Paris. After his visits to Russia with Lou Andreas-Salomé, Rilke embraced Russia as his spiritual heartland and even wanted to take his wife Clara Westhoff to live there. As it turned out, he moved to Paris instead, and became secretary to another artist, who will be featured in future posts here at this blog. ~ RuthLeonid Pasternak paintings on posts January 1-14